Treaty 2 Territory- For more than a 150 years, Indigenous children were forcibly removed from their homes and sent to church-led Indian Residential Schools where they were forbidden to speak their language or practise their culture. But how do you talk about Canada’s cultural genocide with children today?

For generations, the full history of Canada’s residential schools, which existed for more than a century and housed 150,000 First Nations, Métis and Inuit kids with the flat-out mission of assimilation into white society, was suppressed and ignored. If you’re non-Indigenous, you may have had some hazy idea of “Indian schools,” but the kind of nightmarish abuse, bullying, deprivation and death that went on? It was rarely acknowledged and never discussed. I can remember first hearing about the schools only about 20 years ago in a summer course I took and remember thinking, “I have an Education degree…how is it even possible I’ve never heard of residential schools?”

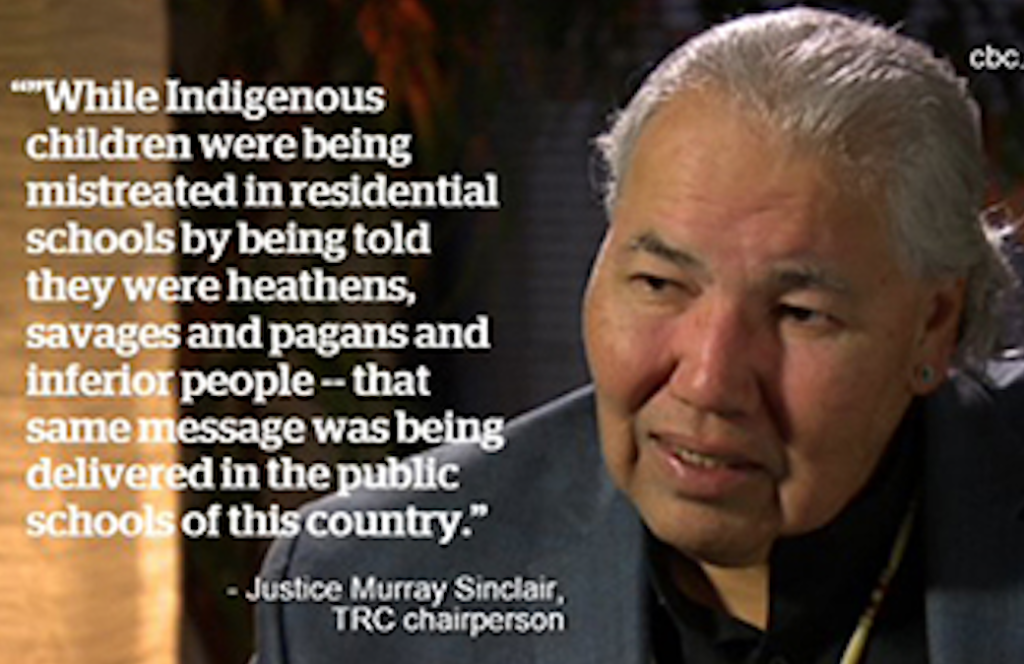

Seven years ago, in 2015, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) issued 94 calls to action to address the legacy of residential schools and move toward reconciliation. I still can’t quite figure out what reconciliation could or should look like in everyday life; it’s one of those slippery words that can mean a thousand different things to a thousand different people. Maybe, then, we should pay attention to the truth part first. As Pamala Agawa, a curriculum coordinator for First Nation, Métis and Inuit education (FNMI) at York Region District School Board in Ontario, told me, we need to figure out the truth for ourselves: “What biases do we carry; what learning do we need to do to better understand the true history of the country?”

Chances are, your own kids are learning about residential schools in class this year. In the TRC’s calls to action, points 62 and 63 specifically call on schools to deliver age-appropriate curriculum about residential schools, as well as Indigenous culture and treaty education, to students in kindergarten to grade 12. It’s not a quick and easy item on a to-do list. How do we talk about Canada’s cultural genocide with our kids? How do we tell them about what this country did to families?

Charlene Bearhead, the former education lead for the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation, has thought about those parent-kid conversations a lot. “Our children are going to grow up with this truth, whether we’re ready or not,” she says. “The best thing we can do as parents is find the courage, and know that it’s not going to be easy and it’s not going to be things that we want to hear. But it’s things that we need to hear, and so we can all learn along with our children.“

Our kids are going to be paying attention to how we talk about this, too. “There’s nothing in the calls to action that calls on parents, and yet parents are among the most important people in a child’s life. They are their children’s first teachers,” she says. “When a child goes home from school and talks to a parent, their response is really going to have a major influence on how that child moves forward with what they’ve learned.”

Teaching the teachers ………..That can feel daunting as parents, but we’re all in this learning curve together—teachers, board trustees and superintendents are learning this along with the kids. “Educators have to relearn what they think they know about Canada,” says Melissa Wilson, coordinator of Indigenous education at the Peel District School Board in Ontario. “For instance, we talk about what it means to be Canadian: We’re multicultural, everyone is welcome to this country, we believe in spreading human rights around the world. It’s not that that story is incorrect; the problem is that story is very incomplete. It doesn’t speak to the story of how Indigenous peoples have been treated in Canada.”

It’s essential, to deal with the tough stuff in age-appropriate ways. If a child’s primary reaction to a book or video or illustration is one of upset or fear, then those emotions may become a barrier to learning. To that end, in the younger grades, teachers introduce the topic through books and stories, and then ask kids about something special to them and how they’d feel if it was taken from them, using phrases that kids can understand, like “not right” and “not fair.” (In older grades, students talk more in depth about the devastating ripple effect that the abuse and loss of culture has on Indigenous communities.)

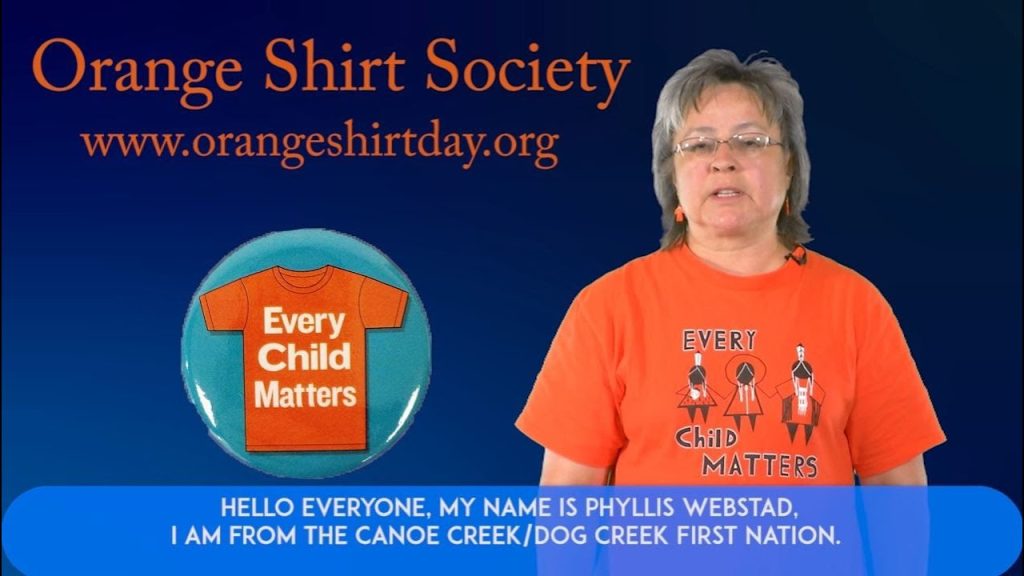

A personal story that resonates with kids is about Phyllis Webstad—and it sparked the national movement of Orange Shirt Day, held annually on September 30. In 1973, six-year-old Phyllis was excited about going away to school and she picked out a new orange shirt. When she arrived at school, all her clothes, including her orange shirt, were taken from her. “The colour orange has always reminded me of that and how my feelings didn’t matter, how no one cared and how I felt like I was worth nothing, explains Webstad. Orange Shirt Day’s message is that every child matters.

The legacy of residential schools—those strained and broken threads of relationships and culture and identity—is like a widening tear in a piece of fabric. If we have any hope of patching it, we’ve got to listen, really listen, to Indigenous stories and experiences, and then talk to our kids. The biggest measure of success for me is about how families are talking about reconciliation at the dinner table, when no one else is listening, When we see that shift happening there, that’s when I believe we’ll be on the road to reconciliation as a country.

Adapted from a 2018 Article by Bonnie Schiedel, featured in “Today’s Parent.”

Renée McGurry, Earth Lodge Development Helper

lodge.fnt2t.com